Emperor Hadrian is perhaps best known for building Hadrian’s Wall in Roman Britain, as well as his male lover Antinous, who drowned in the River Tiber in Rome, causing immense grief to Hadrian.

Although Hadrian is one of Rome’s best known emperors, his family actually came from Italica – a Roman province just outside Seville in Spain, which it is possible to visit today. Hadrian was born on 24 January AD 76 and his mother, Domitia Paulina, was the daughter of an Hispano-Roman family from Gades (Cádiz), many of whom were senators. He only had one sibling – an elder sister, Aelia Domitia Paulina.

Hadrian’s father was also from Italica in southern Spain. Publius Aelius Hadrianus Afer, was a senator of praetorian rank – praetors were important officials who administered justice and also formed part of the military system. The much feared Praetorian Guard was Ancient Rome’s elite force that comprised military intelligence officers and bodyguards to the emperor. So Hadrian was born to a family that held aristocratic status – and to a father who dished out justice. Crucially, as part of the praetorian class, his father was also a soldier. Emperor Trajan was Hadrian’s cousin, who was also born in Italica. It is also thought that Emperor Theodosius (ruled AD 379-395) was also born there on 11 January AD 347.

Italica was the first Roman settlement in Spain, situated just outside the small town of Santiponce, a short bus ride from Seville these days. The Roman general Scipio had founded Italica in 206 BC – and it soon attracted migrants from Italy, including Hadrian’s family, descended from the Aelia who came from Hadria in Abruzzo, Italy, originally.

Hadrian’s father had had a distinguished military career and especially in Africa – his last name ‘Afer’ was actually a nickname given to him after his success in Africa. It is clear that Hadrian had exactly the right family credentials to become a leader in the Roman Empire.

He married Emperor Trajan’s grand-niece Vibia Sabina, who was Hadrian’s second cousin. Roman aristocratic ruling families frequently married family members to protect their dynasty.

It was also not unusual to find reasons to dispense anyone who threatened the power of an emperor. Hadrian provoked the hostility of his own Senate soon after becoming emperor, when he put to death four senators he felt might threaten his own power. He was diligent in visiting every part of his empire and was known for his enthusiasm for building – including Hadrian’s Wall in what was then known as Britannia. In Rome, he rebuilt the Pantheon and the Temple of Venus – and it is also thought he might have rebuilt the Serapeum of Alexandria in Egypt.

His military campaigns were limited, however, considering his family background – he was criticised for abandoning territorial gains made by his cousin, Trajan, in Dacia, Mesopotamia, Armenia and Assyria.

Hadrian’s marriage did not produce any children and in AD 138 he adopted Antoninus Pius and named his as his heir, also naming his successors. Hadrian’s health deteriorated and he died at the Roman leisure resort of Baiae – known as a resort where Romans enjoyed debauched holidays – in AD 138.

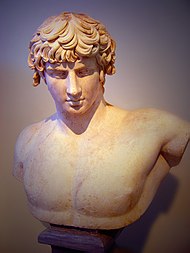

Hadrian’s sexuality has always been a subject of debate – it seems the love of his life was the Greek youth Antinous, whom he paraded in public quite openly. Roman men sleeping with other men was not unusual – what we call bisexuality was not uncommon among men and women in Ancient Rome. But parading a lover of the same sex in public – and especially for an emperor – wa sensual. It is said Hadrian ”wept like a woman” after Antinous drowned – and he immediately deified him, linking him to the Egyptian cult of Osiris.

There is also debate over how Hadrian treated his wife – some sources claim he had great respect for her (she was his second cousin, after all); others claim that it was Hadrian who drove her to suicide, after treating her like a slave.

Whether he was what we now call “gay” or “homosexual” and could not bear the confines of a traditional marriage, we do not know. But the one thing Hadrian will always be known for is his wall, defining the boundary of Rome’s northern territory in Britannia. It seems the only aspect of his life he refused to set boundaries for was his love for another man.

Read my blog about how I marched to Italica myself…almost.

See more of Italica’s ruins, which you can visit if staying in Seville, at Andalucia.com

Buon viaggio!

Featured image: Castel Sant’ Angelo, Rome – originally built as the Mausoleum of Hadrian